OSS Commercialization

Overview

The commercialization of open-source software refers to the process of transforming open-source technology, services, and related components into profitable business models through various strategies. This enables economic value creation and sustainable development. The commercialization capability of open-source software is a crucial driving force for the sustainable development of software and its ecosystem. At the same time, it represents one of the most challenging aspects for open-source software enterprises in their growth journey.

In previous editions of the Open Source Annual Report, the commercialization section was presented as a comprehensive research report, authored by Mr. Xu Zhixing, who was then an investor at Yunqi Capital. The report was detailed, objective, and insightful, providing valuable research material for China's open-source industry.

This year, the commercialization section is organized in an interview format, featuring conversations with four investment and financing experts specializing in open-source technology, infrastructure software, and cloud services. They are Xu Zhixing (Guofang Innovation), Liu Jingyuan (Delian Capital), Ding Ning (INP), and Liu Chao (Atypical Ventures). Through these interviews, the report summarizes and analyzes the development of the open-source software sector over the past few years and provides insights into the future of the capital market. The experts also openly share their personal perspectives and understanding of this field based on their career experiences, as well as their views on the commercialization and growth of open-source enterprises.

1. Using open source as a tool, focusing on strengthening core capabilities to weather the winter together

Guest Speaker: Xu Zhixing (Guofang Innovation)

This interview with Xu Zhixing delved into critical areas including infrastructure, cloud services, and open-source technologies, encompassing investment trends, the future of software development, and the application and evolution of AI technologies. It also explored his perspectives on the relationship between capital momentum and economic cycles, along with the challenges the current business environment poses for startups and venture capital.

During the discussion, Xu particularly highlighted the fundamental differences between China and the U.S. in software commercialization and user payment behaviors, while noting that AI and open-source software are bringing glimmers of hope during this industry winter. He emphasized that the future of software may transcend traditional business models, shifting toward more intelligent services and applications. Despite numerous challenges, Xu maintains an optimistic outlook on the tech industry's future, believing sustained innovation and technological advancement will remain the key drivers of industry growth.

1.1 Recently, the capital market's investment in open source has become more cautious. What are the contributing factors? Is the future outlook positive?

The current capital environment is closely tied to economic cycles. Many factors affect not only business entrepreneurship itself but are also intimately connected with the overall economic environment. For instance, since the 2008 financial crisis, China's foreign trade conditions and globalization process have undergone significant changes. Currently, the overall business environment is unfavorable, with companies generally maintaining cautious attitudes, and credit conditions have notably tightened.

Although AI technology shows broad prospects, North America will fare relatively better due to its more favorable financial markets and economic conditions, and is currently in an interest rate reduction cycle with abundant innovation resources.

In contrast, domestic fundamental innovation resources in China are less abundant, and combined with widespread cautious sentiment, there are limited areas for sustained growth. Therefore, from a long-term perspective, driving innovation indeed faces considerable challenges.

1.2 How should enterprises and startup teams seek new sources of support and resources?

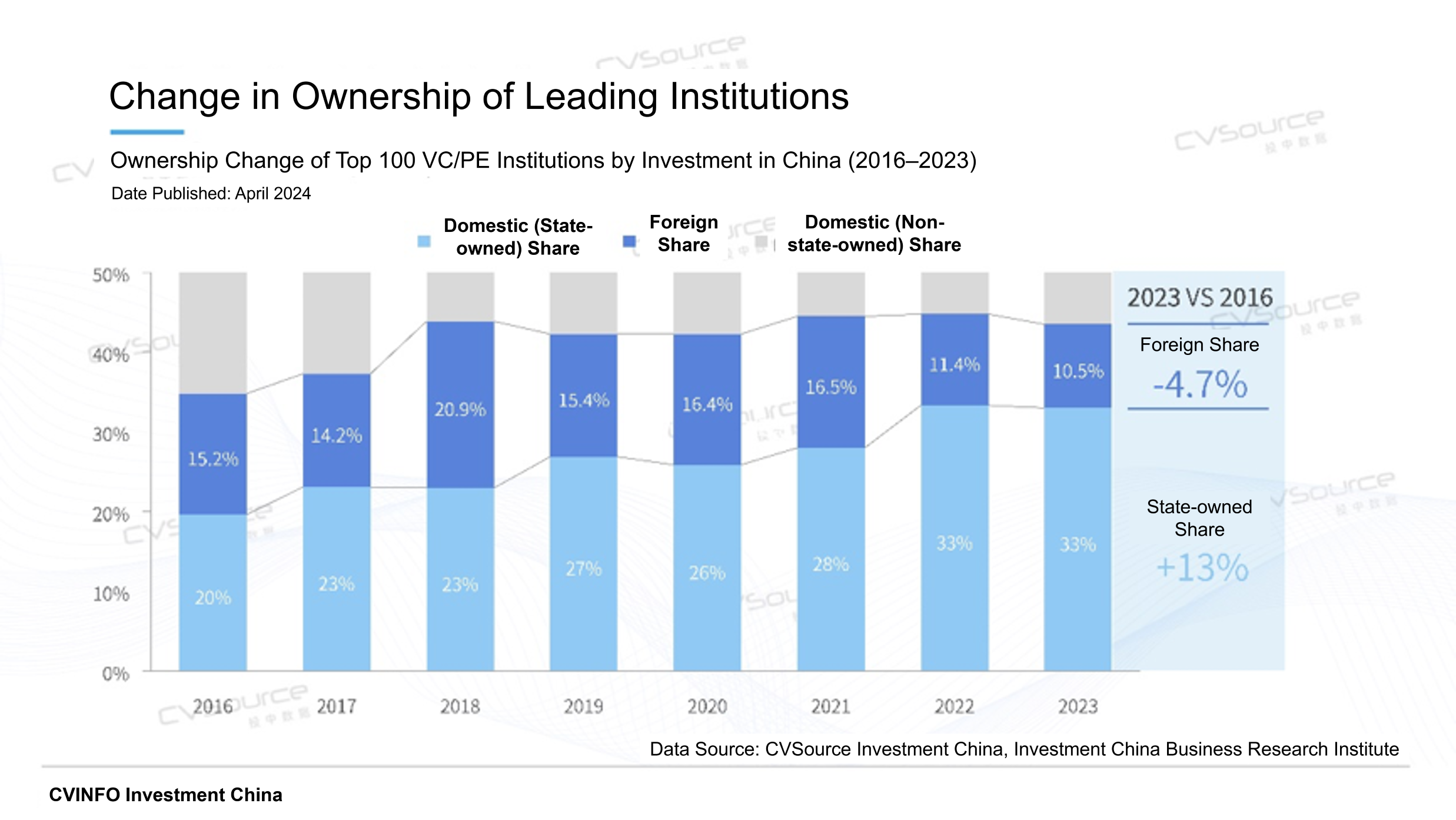

First, in the field of venture capital, I have a profound realization that China's venture capital market, especially the equity investment market, is undergoing a massive transformation.

This change is not even cyclical. Because certain financial models are cyclical under fixed patterns. After analyzing numerous business models, we found that China's primary market is also experiencing significant changes. The typical approach in the past was to imitate or directly copy Silicon Valley's model. Venture capital, particularly technology-focused venture capital, originated from Silicon Valley. In the past, we followed this business model, used USD funding, and even these funds came from the United States, following American investment logic, and continued this process.

However, the situation today differs from the past in several ways. First, the development cycle of domestic tech innovation companies has changed and is no longer synchronized with that of U.S. tech companies. Additionally, tensions in U.S.-China relations have even affected the technology sector. The legislation from early this year had a severe impact on USD investments, leading to funding shortages in certain domestic sectors. However, this doesn't mean that investment demand in tech innovation has decreased; in fact, it's still seeking new forms of support, which everyone is exploring.

Due to the growth of domestic economic strength, some local RMB-based tech investment institutions have emerged. This has led to a shift in investment methods, transitioning from previous USD investments to RMB investments. Although RMB investments currently face difficulties and challenges, this transformation is occurring with increasing support from local governments. This is an exploratory process, and the future shape of domestic primary market equity investment is becoming unpredictable. Similar to the "fixed investment" phenomenon discussed in the primary market, where investors' returns upon exit depend on their business model, products sold, and raw material costs.

Changes in the domestic secondary market and overall financial environment have further influenced this phenomenon. Therefore, I believe this change manifests in the early-stage tech sector as a search for what kind of capital or energy injection is needed.

RMB funds seem to be leaning more towards RMB-dominated investments, which is also a form of exploration. Clearly, this no longer follows the past USD investment model but requires finding new ways to optimize the entire process, which is a challenge facing current practitioners. Overall, these changes in the primary market have led to funding shortages, making the situation very different from previous years.

So, the question of what to rely on if not venture capital becomes a good one, and I think periodically it still depends on downstream users in the actual business cycle.

I believe China's capital market and early-stage tech investment sector will undergo transformation. This requires our collective exploration. Investment is not just a unilateral action by investment institutions but requires growing together with invested companies. We need to explore development paths suitable for China's conditions together.

Therefore, at this point in time, there are clear divergences in people's views. For example, if an entrepreneur's current idea is to focus on overseas markets - a pure overseas strategy - that's also a form of exploration. However, if they want to maintain the possibility of entering the Chinese market, which is massive and has its unique characteristics, then the development path in the Chinese market and the matching of investment-side resources are issues we need to explore together.

1.3 Does that mean it's essential to formulate a commercialization plan as early as possible?

I think commercialization should be done earlier, or perhaps we shouldn't call it commercialization. It used to be called PMF (Product-Market Fit) or achieving a viable financial model. Recently, I've been communicating with colleagues in North America, and even though their economic environment is better, everyone is very pragmatic, having experienced things like the internet bubble.

Currently, investment projects mainly fall into two categories. In the US, except for very high-profile founders or teams, most projects need to demonstrate actual growth potential, meaning looking at the actual operational data of your product over a period of time.

The North American business environment is better because many small companies can easily find seed users. Many YC projects often start charging after operating for a short period - this is fundamental. Then they look at whether there's an opportunity to scale up future revenue, not just relying on the founder's dream alone.

The same applies domestically. If you have some validation at a certain stage, then the next step is to verify scalability. While the team is still small, there should be opportunities to see growth trends, and development should no longer rely solely on investor money but should be supported from multiple angles. Although funding might give companies some initial financial advantages, care must be taken not to cultivate a habit where users expect everything for free. There was a negative atmosphere before where early-stage companies were supported by investors, so users thought they could get all resources for free and would only pay once the platform succeeded - this also wrongly influenced customer expectations.

Under the current unchanged macro environment, both resources and capital have their costs. We need to consider how to perform well under these conditions. Of course, changes might come in the future. Interestingly, these changes themselves provide us with new opportunities.

1.4 In the past year, foundational AI models have attracted developers and customers through 'free' offerings and 'price wars.' Could this once again imply a culture of free usage, impacting the willingness to pay for software?

Indeed, this is very typical. The consumer (C-end) market has its unique business model. Many enterprise service software targets the business (B-end) market, but in China, there exists an intermediate layer in the core market dominated by small and medium-sized B-end clients - the so-called "small B serving large C" model, or professional developers serving professional users. The existence of this intermediate layer is a factor in market transformation. For instance, when services are closer to the C-end, they might face the "free-riding" phenomenon, which not only challenges service providers' survival but also reduces their willingness to pay. However, when the market environment improves and these service providers' own profitability and operations get better, they might show more willingness to pay.

This phenomenon is particularly evident in the market differences between China and the United States. The core difference between China and the US lies in their software payment structures. In the software dimension, the majority of revenue comes from state-owned enterprises and central government enterprises, showing an inverted pyramid structure, where they contribute a very high proportion of payments. Although small and medium-sized organizations are numerous, their contribution to business is relatively limited.

This structure makes the stability of the foundational market rely heavily on the support of top-tier enterprises. The characteristics of these enterprises are that they possess strong bargaining power, which may require a higher proportion of services or customized solutions. This stems from the differences caused by their significant influence. In contrast, the payment structure in the North American market may not be a perfectly upright pyramid, but at least its mid-tier enterprises are larger in scale and more stable, which enables a stronger compounding effect.

The existence of open source is fundamentally because it is still software. However, what we are discussing today is not just open-source software but the challenges faced by the domestic software ecosystem. Why do people consider software to have high gross margins? This is because, compared to manufacturing, software theoretically has higher replicability. A piece of code or a copy can be provided to everyone without additional costs. This is the reason for high gross margins—there is no need for repeated costs. However, this replicability mainly exists in horizontal replication scenarios, while among top-tier enterprises, replicability is relatively low.

Essentially, the cost advantages truly inherent to software production are not as significant. In the North American upright pyramid model, the mid-tier layer is relatively robust. However, this segment is relatively small domestically, resulting in lower stability, and there is still a need to change user habits. Moreover, the domestic market faces a low degree of marketization. Theoretically, it should operate on a survival-of-the-fittest principle—if you perform poorly, you are eliminated. But even when a company disappears, the demand still remains.

1.5 Are there more opportunities in the AI field?

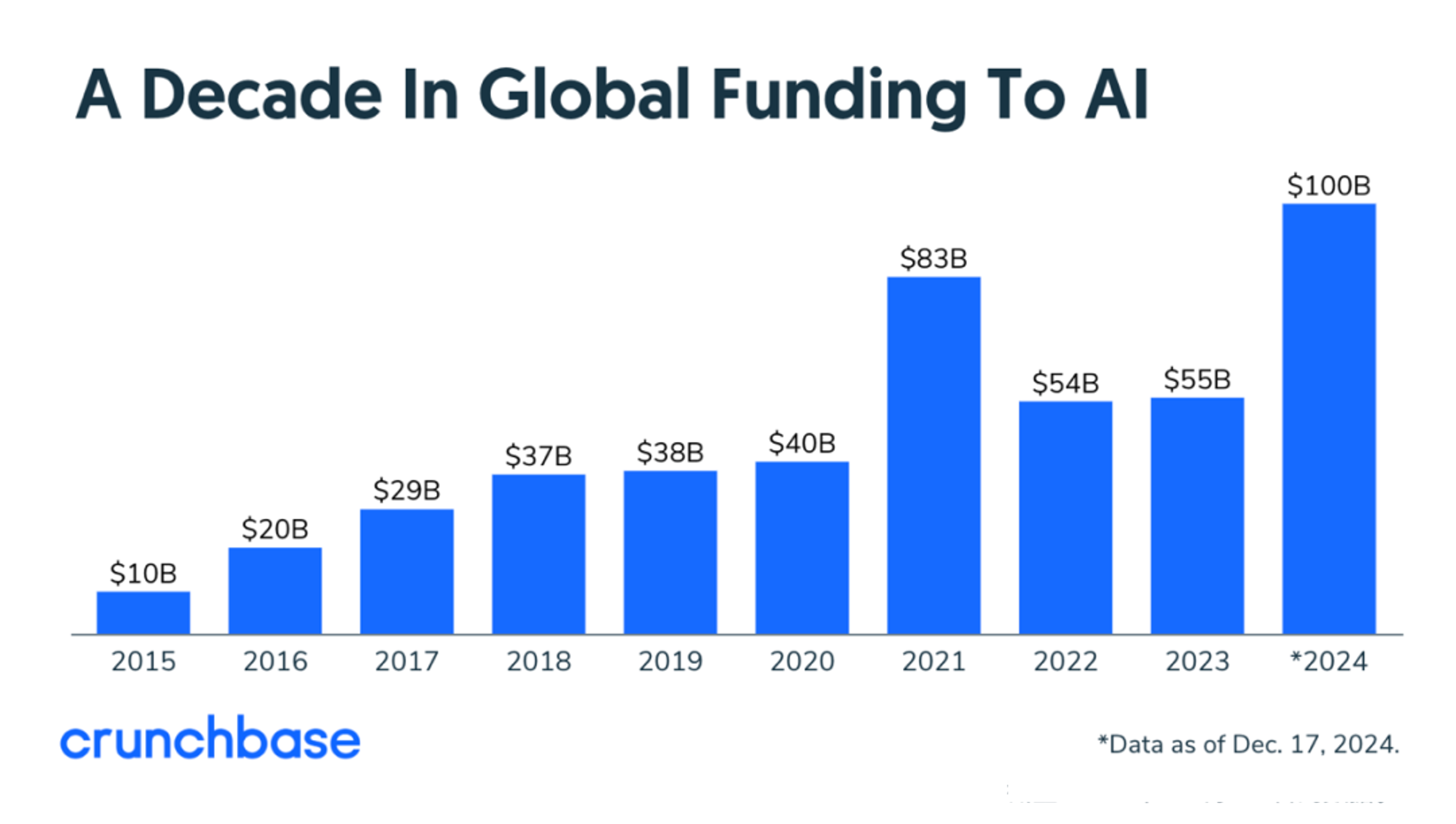

First, we have the foundational large models. At present, both open-source and closed-source models are worth continuous attention.

Moving up one layer, there is an intermediate layer often referred to as AI Infrastructure, which sits above the models and below the applications. This is a typical layer with high developer engagement. Open source has always been highly beneficial to the developer ecosystem, so there is relatively more open-source activity in this layer.

Further up are open-source applications, which are AI-based applications. Currently, in the field of AI applications, while there are already some open-source projects, they are not very numerous and still require further development.

In the foundational software domain, particularly in segments similar to traditional intermediate layers, the overseas market is notably active, especially when distinguishing between domestic and international business. This activity stems from a simple fact: even before AI infrastructure became widespread, North America had already seen some relatively successful cases of commercialization. These cases have at least provided the industry with a clear development path and potential opportunities. This layer shares some similarities with traditional data infrastructure but sometimes also involves more niche and vertical domains.

Even so, a mature product ecosystem can only emerge after the broader ecosystem is well-established. For this reason, the domestic market faces even greater challenges. This is just my personal perspective, but it is undeniable that even in such an environment, startups maintain a certain level of enthusiasm. They are actively seeking funding and have gained considerable recognition from investors. In the future, it will be important to continue monitoring the development of leading companies in this direction.

1.6 In the middle layer of the AI field, there are many niche directions. How can companies and teams identify a long-term, sustainable direction rather than a short-term or transitional solution? Is there a possibility of future monopolization by major cloud providers?

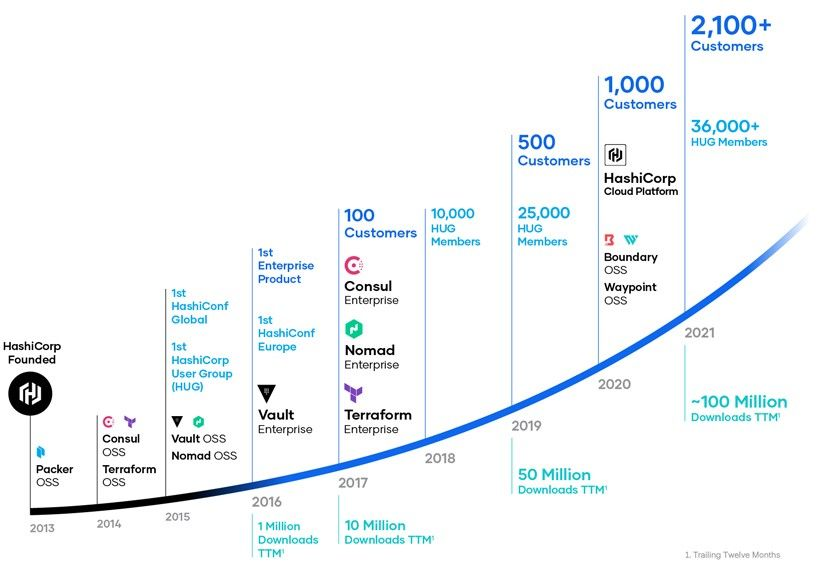

I personally believe that this does not necessarily involve direct competition with major cloud providers, but it will eventually lead to differentiated competition. You won’t just think of yourself as competing with a specific company; you will also be competing with large cloud providers, some application vendors, or developers. This is similar to companies like HashiCorp in the U.S., which have developed their own commercialization by building a product matrix based on brand and recognition. So, is there an opportunity in the domestic market to achieve such integration and develop a more complete product portfolio, thereby gaining an advantage in the intermediate layer? If you cannot integrate and build a comprehensive product system and instead only offer a single product, then when other companies achieve better systems and ecosystems, your value and significance will become challenging to sustain. For example, in the field of Data Infra, there has yet to be a clear leader in the domestic market.

If this issue is not addressed, particularly in the area of AI infrastructure, I believe it is not just a problem for major cloud providers—it could also involve large model companies or other typical IT companies stepping in to cover these areas. Ultimately, this is still a matter of user ecosystems. The key is who can establish a complete and systematic solution earlier. From the perspective of developers looking at the problem from a user’s point of view, my initial demand is the effectiveness and applicability of the solution. When the effectiveness is similar, I would then consider factors such as ease of use and ecosystem support. In essence, it’s quite straightforward—what do users need?

In the early stages, there may be a first-mover advantage, where other people or companies have not yet developed the product. For example, in the beginning, there were limited product options in the market, and domestic players didn’t have many choices. Or, during the effectiveness phase, some products performed reasonably well, which constituted a first-mover advantage. Nevertheless, relying on these initial advantages still requires further progress.

Thus, the core issue is to return to the essence of software. I believe that the essence of software, including open-source software, lies in the need for rapid iteration. In the past, users purchased software through a one-time buyout, only needing to acquire a single copy. However, as users are no longer satisfied with simply owning a copy, they now expect software to be continuously iterated. With the acceleration of software development and agile development, the subscription model has emerged because users are not just purchasing the right to use the software but also ongoing services and updates.

For open-source software companies, what they provide is not just the initial code or related products but also the ability to continuously iterate. Some entrepreneurs believe that those who purchase open-source projects are essentially buying the team’s ability to iterate and their capacity for agile development. This is the true essence behind the software.

Returning to the earlier discussion, if your intermediate layer needs to have characteristics similar to HashiCorp, it must continuously possess the ability to iterate and expand. Interestingly, the upper-layer applications are actually undergoing transformation and disruption. From my perspective, the core issue of what was previously referred to as "SaaS"—software as a service—lies in how to distinguish between "service" and "software." Many companies provide SaaS, but what customers are really purchasing is still the software. The key is how to enable users to master and utilize that software.

1.7 Are you optimistic about the overall entrepreneurial environment in the next phase? Which directions are more likely to experience rapid growth?

Regarding the impact of the AI era on upper-layer applications, I personally hold an optimistic view, believing that it could bring disruptive opportunities. This concept was previously referred to as "Software 2.0," which essentially means enabling software to provide more than just services through intelligence. Taking SaaS as an example, in past scenarios, users needed someone who knew how to use the software to orchestrate processes, whether online or offline, whether through SaaS or other methods. However, in the future, AI will be able to more accurately handle more stages, replacing human operators and some professionals, thereby providing services directly to intermediate-level users.

Especially in the domestic market, there is a typical phenomenon: why are domestic software companies not as competitive as those overseas? One reason is that labor costs in the domestic market are relatively low, leading to a typical outsourcing model. However, I believe AI has the potential to integrate some of the functions of outsourced services into software, enabling software to utilize these services more efficiently. Of course, this also requires consideration of cost-effectiveness.

Why compare with overseas markets? Because labor costs are higher overseas, they reached a certain cost-performance balance earlier. However, with the improvement of AI capabilities, domestic software companies may achieve a kind of reverse pressure mechanism through software capabilities. This means that companies that previously only engaged in outsourcing or development may now be able to provide more value. I believe AI will change the software ecosystem at the application level, especially as there are many opportunities in software applications. This will require iterative updates of foundational model capabilities as well as overall software design.

1.8 What are the key observations regarding the most closely watched AI programming trends?

AI programming can be divided into two aspects: first, the impact of AI programming on programs; second, the application state of AI programming as a product itself. For programmers, if their work is limited to the compiler stage, then AI programming serves more as a cost-reduction and efficiency-enhancing tool. As AI capabilities improve, if efficiency advances to the level of development paradigms—like the paradigm shift I mentioned earlier—then challenges will also arise. Ordinary programmers will need to find their value output points based on these paradigm changes or be compelled to upgrade their skills.

Indeed, AI not only drives service upgrades but also, to some extent, changes the outsourcing model. In the past, developing a software system required a certain level of expertise, which increased the demand for outsourcing services. Now, intelligent models can integrate this expertise into algorithms, reducing reliance on outsourcing. Today, what is being developed is no longer just a piece of software but an integration of software, human outsourcing, and related services to deliver comprehensive solutions. This has brought about a transformation in the software ecosystem. At the same time, AI coding has introduced new requirements for developers, i.e., programmers, and similarly applies to outsourced development.

I have always believed that open-source software has a certain marketing effect. People don’t use it solely because it is open source but more because open-sourcing has a positive impact on sales and market expansion within the developer ecosystem. Returning to the earlier point, some open-source trends have also emerged in the AI field, indicating that open source can drive systemic changes within the corresponding ecosystem.

In the future, the combination of open-source approaches and existing intelligent capabilities will change the software ecosystem. I believe that the issue of open source in the AI field needs to be analyzed from different levels, so opportunities still exist, but challenges are also present. The application layer is currently in its early stages, but its future growth potential is enormous. In terms of commercialization, AI infrastructure faces significant challenges, although there have already been many successful practices at this stage. As for foundational models, there is a growing consensus on the current state of affairs.

1.9 Will open source continue to play a significant role in driving the software industry forward in the future?

Indeed, I believe the core of open source lies in the process of distribution. I think the open-source ecosystem will always exist and continue to thrive. For example, even today, various forms of trade shows still exist because they remain one of the most effective ways for business roles to acquire customers. Therefore, this model persists.

However, programmers and salespeople are different. For the developer ecosystem, the key is how to effectively reach these types of users. Essentially, it helps product or software companies establish a connection with end users. This is the most fundamental aspect. I have always emphasized that open source is not just about making code public but about using this approach to build a connection with end users—whether they are developers or other individuals. For non-developer-oriented open-source projects, it directly builds a bridge to end users on the business side. Therefore, I believe open source is an effective way to acquire users. Just like in sales, you cannot directly sell a product to a customer; instead, you need to prepare a solution and deliver results.

After reaching customers, the key is how to convert them into loyal users and uncover their commercial value. Nowadays, customers not only need backup software but also expect companies to have the ability to continuously iterate on their products, provide stable systems, and deliver reliable services. Thus, open source is not the end of marketing but rather a starting point. By gaining more examples through open source, the question becomes how to use these smoother communication and engagement opportunities to ensure the success of follow-up work, rather than skipping subsequent steps. For any company, open source actually involves higher cost inputs. Although from a financial perspective, this breakdown may seem challenging, it still belongs to the development domain. From this perspective, the key is how to optimize the balance between input and output, turning it into an effective sales or distribution channel. Once market coverage expands, if these opportunities are not effectively utilized, all efforts become meaningless.

Therefore, I believe that for companies, whether in the early stages or at a mature phase, investing in open source is necessary. In the early stages, brand awareness may be low, and exposure opportunities may be limited. Even so, a small number of exposure opportunities can help you find seed users. Even for companies that are already very mature, these opportunities remain extremely valuable.

Looking at large companies, whether it’s Confluent or DataBricks, these enterprises participate in various conferences every year. During these events, they provide opportunities to engage with users. Interaction is needed at every stage. However, the key is not just holding conferences but whether you truly hear user feedback during these events, identify their needs, and use this information to help your product continuously iterate.

Whether it’s a service or a product, I believe this is the essence of open source—that open source is an added value. When investing in software companies, I don’t add points simply because they are open source, nor do I deduct points if they are not. Instead, if a team chooses to use open source as its strategy, it is a tool and a weapon. The key lies in how effectively it is utilized and executed. You need to provide some evidence to prove that you have this awareness. This is my response to your earlier question about how open source creates value at different stages of a company. Personally, this is my perspective.

1.10 Open source is an investment for companies. For early-stage companies, how can they balance this investment?

If you are currently a startup, such as a development team of around ten people, with eight or nine of them focused on development, they may lack the necessary skills to carry out tasks like business development, attending conferences to share insights, or collaborating with the sales department. These responsibilities present a challenge for development teams in open-source projects to balance their workload. You need to decide how much time to allocate to sharing and interaction versus how much time to dedicate to coding.

However, we do not simply view open source as a customer acquisition tool; instead, we consider it as part of the production process. Due to the domestic business environment, when large companies intend to purchase our products, they require a more stable version and may even expect us to address specific issues for them. As a result, we ask these large customers to adapt to our open-source version as much as possible, synchronize bug fixes, and optimize functionality. Our goal is to provide excellent customer service and generate more revenue from these customers.

I believe that whether domestically or abroad, large customers have specific needs. For example, Snowflake invests heavily in large customers, both in terms of sales and service. At this level, the role of the product manager becomes particularly important.

When feedback is returned, we discuss which issues must be addressed because maintaining commercialization is our goal. At the same time, we identify which problems are more universal versus those that are specific to certain customers. This requires a clear perspective on feature definitions. With limited resources, it becomes a balancing act—how to balance meeting the needs of large customers with addressing broader market demands. In theory, all these needs are important; the key lies in whether we have sufficient resources to implement them.

Personally, I believe that the company's CEO, as the top leader, needs to possess the capabilities of a so-called "chief product manager" to a large extent. As the person steering the ship, the CEO determines the company's development direction. Of course, this balance is ultimately decided by the CEO. At certain stages, the CEO may believe that in the current business environment, simply serving large customers well is sufficient. In this case, the open-source project may become more of a byproduct, with more effort focused on meeting the customized needs of large customers. However, if my core goal is to create a replicable, distributable product, I may choose to focus on refining the open-source project during certain phases.

Therefore, someone needs to take the lead. While the CEO can take responsibility for the product, given the CEO's heavy workload, I believe there still needs to be someone like the CEO who dedicates enough effort in this area. This is my personal perspective.

2. When benchmarking against the U.S. loses its relevance, Chinese open source should find its own rhythm

Guest Speaker: Liu Jingyuan (Delian Capital)

Jing Yuan has experienced both USD funds and RMB funds investment environments and possesses extensive expertise in cloud services and infrastructure. In her discussions, Jing Yuan provided an in-depth analysis of the role and impact of open-source projects and the open-source spirit within the modern technology ecosystem. By citing multiple examples of open-source companies, she explored how the open-source model drives product innovation and enhances market competitiveness.

Furthermore, the discussion focused on evaluating key metrics for open-source projects at different stages, such as community activity, user growth, and financial stability, highlighting the importance of being market-driven and solving real-world problems for the success of open-source projects. At the same time, challenges faced by open-source projects during commercialization were examined, such as differences in copyright perceptions and recognition of market value. While maintaining an optimistic outlook on the open-source field, Jing Yuan emphasized the necessity of rationally assessing the commercial potential of open-source projects and encouraged continued investment and attention in this area.

2.1 Recently, the capital market has become more subdued, and the enthusiasm for open-source software has also waned. How should we understand and assess this shift in market sentiment?

In the past, many people liked to benchmark against overseas companies, especially those investors primarily dealing in USD-based investments. They tended to adopt a more opportunistic approach to researching companies or industries. They would conduct industry analyses on companies across different technological layers in the U.S. and use this as a basis to evaluate the status of a company. This method gave them confidence to assign relatively high valuations to companies.

We believe that they ultimately succeeded, going through a successful transition from open source to commercialization. Based on certain multiples, we conducted valuations. At that time, the U.S. stock market gave open-source companies relatively good valuations, and several of them were performing quite well. These formed part of our information sources.

In the investment market, another factor is actually determined by supply and demand. At certain stages, investors often feel compelled to invest in specific categories of open-source projects, particularly those with a technical focus. In reality, most open-source products have evolved into infrastructure products.

For pure SaaS application products, open-source components are relatively scarce. As a result, the development cycles for infrastructure products are typically longer. The barriers to entry for starting such projects are inherently high, so the number of founders capable of launching such projects is limited. This leads to a scarcity of such projects in the market, which in turn causes competition among investors for the limited number of projects, driving up asset prices. For example, in the case of real-time data warehouses like StarRocks, there are usually only two or three such projects, and I must invest in the one I consider the best. In such situations, numerous institutions compete for the few high-quality projects, leading to rising prices. I believe this high pricing is primarily reflected in two aspects: the scarcity of the projects themselves and the intense competition among institutions.

Later, did capital markets realize this? I think PingCap is a good example. Because it has always been a leader in the industry, it has garnered widespread confidence. Around this time, institutions began to realize that there might be overly high expectations for open-source infrastructure products, or that simply benchmarking against similar U.S. products might not be applicable.

The primary reason is that after investing, they found that revenue growth was not as expected. After making an investment, we typically expect the company to exhibit a certain conversion rate and growth curve. However, when we found that the company did not change as quickly as expected post-investment, it might still be focused on technical iteration. This was one scenario. Later, we noticed that even though the company began attempting commercialization, the actual pace of commercialization did not meet expectations. Revenue did not significantly increase, and in some cases, there was no noticeable growth even after several years. The company showed a trend of slow growth, lacking the explosive growth that was anticipated.

At the same time, there was a vicious cycle of iterative processes. Due to the lack of significant growth from commercialization, the company found it challenging to secure the next round of funding. The cautious use of funds meant that the company might not be able to advance hardcore products like PingCap solely through a PLG (Product-Led Growth) strategy. It might need to pivot to an SLG (Sales-Led Growth) strategy. Adopting an SLG strategy would mean the company needs to hire sales and local business personnel, which requires financial investment. Given the difficulty of raising funds, coupled with potentially high valuations that deviate from the company's fundamentals, spending becomes even more cautious.

Moreover, an overly cautious financial strategy may impact business development, slowing revenue growth. In such cases, the company struggles to achieve rapid growth and can only promote stable business growth over a longer period, such as one or two years, to gradually bridge the gap between valuation and fundamentals. Once this process is complete, the company can shed the early-stage bubble and enter a healthier financing and development cycle.

2.2 Early-stage open-source companies invest more time and resources in refining their products. How do investment institutions view software companies with longer growth cycles? Do they prefer an earlier commercialization phase to validate the product?

I believe this issue can be divided into two parts for discussion. First, how investors view this process. Second, what expectations investors have for the project itself. If investors originally expected the project to have reached a commercialization inflection point, meaning there would be relatively fast growth afterward, they might feel disappointed if the growth rate does not meet expectations. This is essentially an issue of expectation management.

The second issue is closely related to the complexity of the product itself and also to the investors' understanding. For example, if your product falls under the IaaS category, do not expect it to seamlessly serve large-scale customers after just three to five years of development. This is unrealistic, as the problems may lie in poor performance, insufficient stability, or inadequate cost control. Therefore, it is difficult to achieve success in the market in one leap. For mid-layer products, such as databases, data warehouses, or real-time data warehouses, the technical complexity is evident. Developing such products indeed requires a long period of refinement in collaboration with leading customers to address all potential issues and achieve commercialization for the target customer group. Clearly, for some more complex products, small companies are not the ideal customer base.

This is where the difficulty lies: the product must target medium and large customers from the very beginning. For instance, for a database that is primarily distributed and transactional with secondary analytical capabilities, we know who the target customers are. How many customers have distributed needs? They must be of a certain scale. Small customers do not have distributed needs; a single machine is sufficient for them, so they do not require such a product.

Therefore, I believe investors first need to have a reasonable understanding and assessment of the difficulty of the projects they are investing in. Second, during the fundraising process, companies need to communicate with investors to manage expectations properly. This means that companies need to honestly share their development trajectory and seek investors who can understand and agree with this trajectory to collaborate with. In this way, both parties can work together more smoothly and comfortably over a longer period.

2.3 Would this impact investment institutions' willingness to invest in open-source projects or infrastructure software projects?

Let me explain this in two parts. First, I believe this possibility exists, but theoretically, the impact may not be significant. This is because, overall, there are already relatively few investors in foundational software projects, and the size of this group is inherently small.

Why are there relatively fewer investors in infrastructure? This might be because this type of investment is both difficult to profit from and time-consuming, which goes against the profit-driven nature of capital. From a first-principles perspective, this is indeed the case. Beyond this reason, do you think there are some investment projects where the development speed has not met expectations, even though they are growing, but investors feel the growth is too slow? Would this affect investor enthusiasm? I think this issue is manageable because, in my view, if investors are already focused on infrastructure investments and can understand and appreciate this type of investment, they are unlikely to be influenced by external factors and may continue to adhere to this investment strategy.

From a personal perspective, if an investment manager passively evaluates projects—for example, because it is a task assigned by the institution or to meet KPIs, rather than stemming from genuine interest and proactive exploration in a specific direction—then I think such individuals are unlikely to focus on that direction in the long term. Personally, I don’t think this would have a significant impact.

On the other hand, this also affects some institutions. Many institutions have already canceled investments in related directions. Even if individual investors are personally interested in this direction, they must turn to institutions that remain open to this field. For instance, I consider myself fortunate to have been able to transition from Kingsoft Cloud to a VC institution that accepts this direction. If my current institution continues to focus on this field, I will naturally stay; but if it no longer focuses on it, I might have stayed at Kingsoft Cloud. Therefore, I consider myself lucky to have found a platform where I can continue to focus on and invest in directions I am interested in. However, many of my peers may not be able to find institutions willing to embrace this direction.

So, I think solving the issue of institutional selectivity actually requires more good companies to emerge, and for them to gain recognition in the capital market, particularly in the secondary market. This would help rebuild confidence in the primary market. For example, some more grounded companies, such as those dedicated to domestic databases, operating system development, or even middleware companies, as long as they successfully go public on the A-share market and gain favor from institutional investors and secondary market funds after listing, this would, to some extent, inspire confidence in the market for such companies.

2.4 In the current domestic business environment, open-source enterprises face many obstacles. What are the most critical challenges?

Speaking of open source, most open-source projects belong to the infrastructure category, so they naturally have a connection with the former. However, aside from all the challenges faced at the infrastructure level, open-source products may fail to achieve a closed loop in the commercialization process. In China, this issue is particularly severe. On one hand, compared to Western countries, copyright awareness in China is relatively weak. Even if the licensing agreement does not adopt fully permissive terms, commercial use still requires proper licensing arrangements. However, many people still use these products privately and even package them as commercial products to sell to others. This is indeed a problem.

China lags behind Western countries in terms of intellectual property protection awareness, or rather, the penalties for copyright infringement are not severe enough. This has led to issues with overall usage habits, which is one aspect of the problem.

The second point is a more prominent phenomenon in China: many users have copyright awareness but often struggle to provide reasonable prices for the value created by software. This is also an issue. Whether it's open-source or commercial software, they may solve many problems for businesses and provide significant value. However, companies may be unwilling to pay high prices for these products because they regard them as mere software products. In contrast, some hardware-selling companies, despite offering solutions that are relatively minor and incomparable to the value of software products, are able to sell their offerings at much higher prices.

This might be related to systemic procurement tendencies influenced by budgetary mechanisms or the ability to capitalize fixed assets on balance sheets. This, in turn, creates some unfavorable conditions for the commercial expansion of open-source products.

Since commercial software is usually priced higher, the market value of open-source software is difficult for customers to assess. Customers may question why they need to pay for software when there are free options available. They often overlook the actual value that open-source software can bring and that it is reasonable to pay a proportionate fee for it. Overall, the domestic environment for paid software and the system for evaluating the value of open-source software remain unhealthy.

2.5 What key aspects should be focused on in the commercialization process of open-source software?

When commercializing open source products, the primary concern is ensuring that the subsequent maintenance system can keep pace. Essentially, you are offering a freemium service, and this aspect must be executed well. Customers should not pay for a service that performs indistinguishably from the free, open source version.

Thus, the first priority is to develop a systematic strategy for the freemium model. The second critical point is to address key pain points in the customer’s production workflow.

I recall that Fit2Cloud once proposed a perspective (though the exact wording escapes me) emphasizing that core IT personnel across different functions—such as operations, testing, and security teams—should each have access to the best tools within their respective domains. This approach hinges on two principles: Market Demand: The product category must target a clear and urgent need. Product Excellence: The tool must be superior. Mediocre products may only survive as open source, severely limiting monetization potential. Additionally, pricing should be moderate to avoid deterring users. A rigorous cost-benefit analysis is essential, factoring in not just development iterations but also the expenses of building operational and post-sales support systems. Equally important is setting a reasonable price range for customers, which requires careful evaluation.

2.6 How should open-source enterprises evaluate whether to invest resources in international expansion?

Indeed, we should not set limits on ourselves. I firmly believe that if a team is confident in its product capabilities from the very beginning, it can fully adopt a global strategy right from the start. I think "Go Global" is indeed a challenging issue. For domestic companies, it seems they struggle to truly enter the international market. However, venturing into international markets also brings many challenges.

Some early pioneers among domestic software companies going overseas have indeed provided valuable references for overseas customers and markets. Although their overseas revenue is currently quite substantial, it seems to have fallen short of their initial expectations. Therefore, for technology software companies aiming to expand internationally, they still face significant resistance. Since SLG (strategy and long-term growth) is required, this process cannot be completed quickly.

2.7 Is the outlook for open-source software startups and growth still optimistic in the near future?

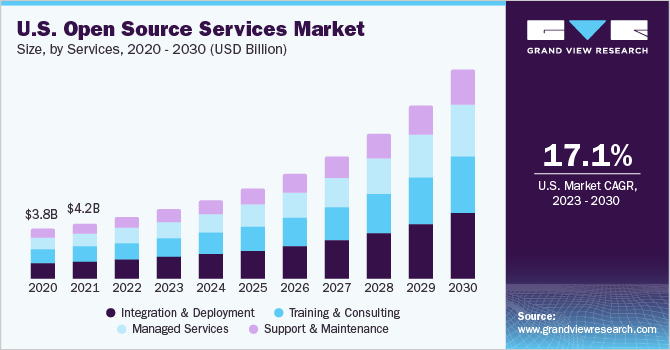

I believe that although the market space appears to be large, the key lies in whether you can capture this space. The foundational software market, including areas such as databases, data warehouses, and large model middleware, is characterized by its technical nature. Virtually all companies, regardless of size, as long as they have IT infrastructure, will use this type of software.

If your primary customer base consists of mid-tier and higher-level companies, then the number of potential customers is quite substantial. The key is whether you can gain market share in these areas. We previously conducted a relatively systematic analysis of the market space for some large-scale projects, and the capacity of these markets is sufficient.

2.8 What can be learned from rapidly growing companies or projects?

Current large models need to establish a bridge with applications. Especially in enterprise-level applications, many consumer-facing (C-end) products may only require building a front-end on top of the model. However, for business-facing (B-end) applications and functionalities, most cannot directly rely on the model to achieve their goals, which is an inevitable trend in industry development. This market is entirely new and holds great potential for the future. Both in terms of time dimension and overall scale, it constitutes a significant market. Moreover, as with previous logic, although the market is vast, the key lies in whether one can capture market share. To achieve this, it is crucial to clearly understand customer needs and strive to meet these needs in the best possible way.

2.9 How can product design align with current real-world needs while avoiding becoming merely a transitional solution?

The point you mentioned, I believe, is something every organization pays close attention to. However, whether they are truly concerned about it is another matter. From our perspective, the product has already undergone significant changes since we invested in it. Take early 2023 as an example: its functionality has evolved noticeably compared to its initial state. I believe that if one day there is a fundamental shift in how we use and interact with large models, the relevant companies should be able to quickly identify these changes and adjust their product forms accordingly. This is because they maintain close collaboration with both customers and large model companies, understanding customer needs and the iterative progress of the models' capabilities. Since they operate in the middle layer, if companies at this level cannot respond to changes, it would be even more difficult for external parties to define new forms.

For smaller open-source projects, on one hand, they often lack the time and resources to treat these projects as independent and sustainable businesses, making effective investment and improvements challenging. On the other hand, many founders may lack a higher-level vision, failing to develop these projects into more robust services. I feel regretful for these products. But in reality, every year, many similar products lose their vitality during their growth process.

In such cases, the key lies in evaluating the alignment between a team's overall resource endowment and the requirements of the proposed project. If the resources required for the project far exceed what the team’s current configuration and capabilities can provide, but the entry point is feasible, I personally think that early collaboration with major companies could be an effective strategy. Launching the product can be a relatively straightforward approach, while being acquired by a major company represents a deeper level of involvement. During the acquisition process, we should strive to maintain a certain degree of independence to ensure the open-source project can continue operating and receive a certain level of resource support each year. This would be an ideal form of collaboration. For those unique and niche products, relying on the support of large platforms might be a better choice.

2.10 What examples do you consider to be healthy open-source projects?

The one we have interacted with the most in the past is probably Red Hat. It is a classic example. Its approach to building sales channels and online sales platforms in China has provided many valuable examples worth learning from.

2.11 What are the characteristics of projects that fall short of expectations?

I want to talk about some projects that I believe have not developed as expected. Where exactly does the problem lie? For example, some companies focus too much on breakthroughs in a single technology but may overlook the nature of market demand. In the current economic environment, such an approach is quite risky unless their projects are purely for public benefit and they are completely unconcerned about whether the product has practical value or whether anyone is willing to pay for it.

In some of the projects I’ve been involved in, it feels like holding a hammer and looking for nails. Due to their exceptional technical capabilities, they developed a very powerful hammer. However, this hammer might be over-engineered for most users—customers don’t need such a powerful tool; they need a more standard version of the hammer. When a product is over-engineered, people tend to opt for more popular and simpler versions. As a result, the market fails to form, which is clearly very dangerous and concerning.

I have another point to add. You mentioned some underperforming open-source projects, and indeed, there are also some founders—this is a personal expectation of mine. Currently, many open-source software projects in China that aim to commercialize are led by founders with technical backgrounds. Therefore, if you want to go further than others, it’s best to find a co-founder with a strong business background to work with you on founding and advancing the project. With your technical expertise, the project might have a better chance of success. This is because founders with purely technical backgrounds often lack experience in navigating complex or harsh business environments. Trying to do everything alone can be quite challenging.

2.12 How can a project be assessed and evaluated? What are the key reference criteria?

At different stages, the evaluation metrics may vary. For example, in the early stages of a project, since we are the first-round investors and there is no revenue to refer to at this stage, we primarily focus on whether the product meets the basic needs of customers. As the project progresses, we pay attention to the operation of the community. It may not be until the project reaches a certain stage that financial and performance data become the main focus. In the early stages of a project, these financial and performance metrics are not the priority. I believe that regardless of the stage of project development, as long as the product remains open source, more attention should be given to the operation of the community. Of course, this doesn’t mean all efforts should be focused solely on it, but rather that resources should be reasonably allocated.

In the later commercial stages of the project, we focus on its customer base. However, I think that during the first year or close to the first year of the project, we do not place significant emphasis on its commercial aspects. Our main focus is on the quality of community operations, as the project is still in the process of optimizing its performance at that time.

Typically, we look at some standard metrics, such as pricing models, whether payments are made annually, renewal rates, user retention, and other conventional indicators. The most noteworthy metrics, in my opinion, are MRR/ARR or the repurchase rate.

3. Only when a single transaction reaches a million dollars can infrastructure enterprises dare to discuss the next steps

Guest Speaker: Ding Ning (INP)

Over the past year, the capital market has shown a particularly cautious approach toward open-source software, with more objective and pragmatic requirements for companies. The INP team, led by Ding Ning, successfully completed several key financing stages for projects last year. In his interview, he provided an in-depth analysis of the role of open-source projects in the growth of software companies and the commercialization challenges they face, emphasizing the importance of open source for sustainability and visibility. He believes that the commercial value of open-source projects must be fully recognized, and ensuring a sustainable development path is the key to gaining broad market acceptance.

The interview also touched on the shortcomings of Chinese open-source projects in commercialization and the bubble phenomenon in the capital market, pointing out that the critical issue for open-source projects is how to sustain development after obtaining initial funding. Ding Ning stressed that long-term product planning aimed at future enterprise budgets is particularly important for startups. Product design must balance the current market budget scale with future demand trends to ensure the company's long-term viability and growth potential. Once a company enters the market, revenue becomes the simplest and clearest indicator to measure whether the product meets demand, whether the technology is robust, and how well the organization is managed.

3.1 When will the next cycle be for open-source software to regain capital attention after the current downturn?

I believe several scenarios may emerge in the future:

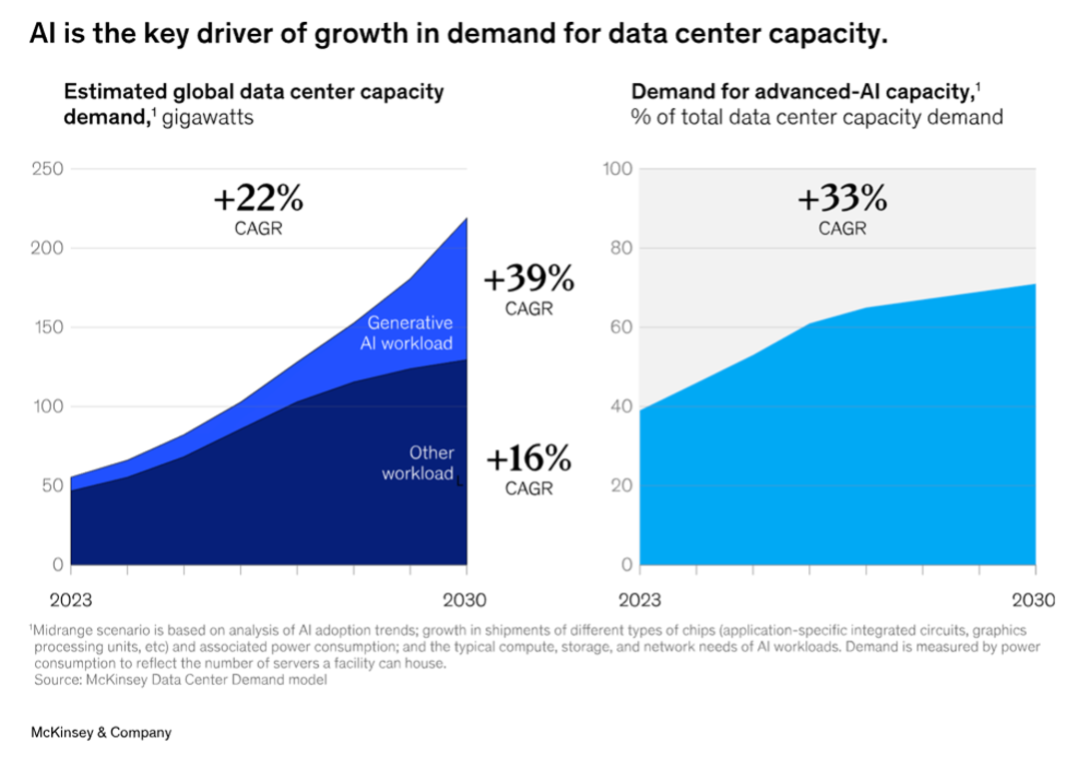

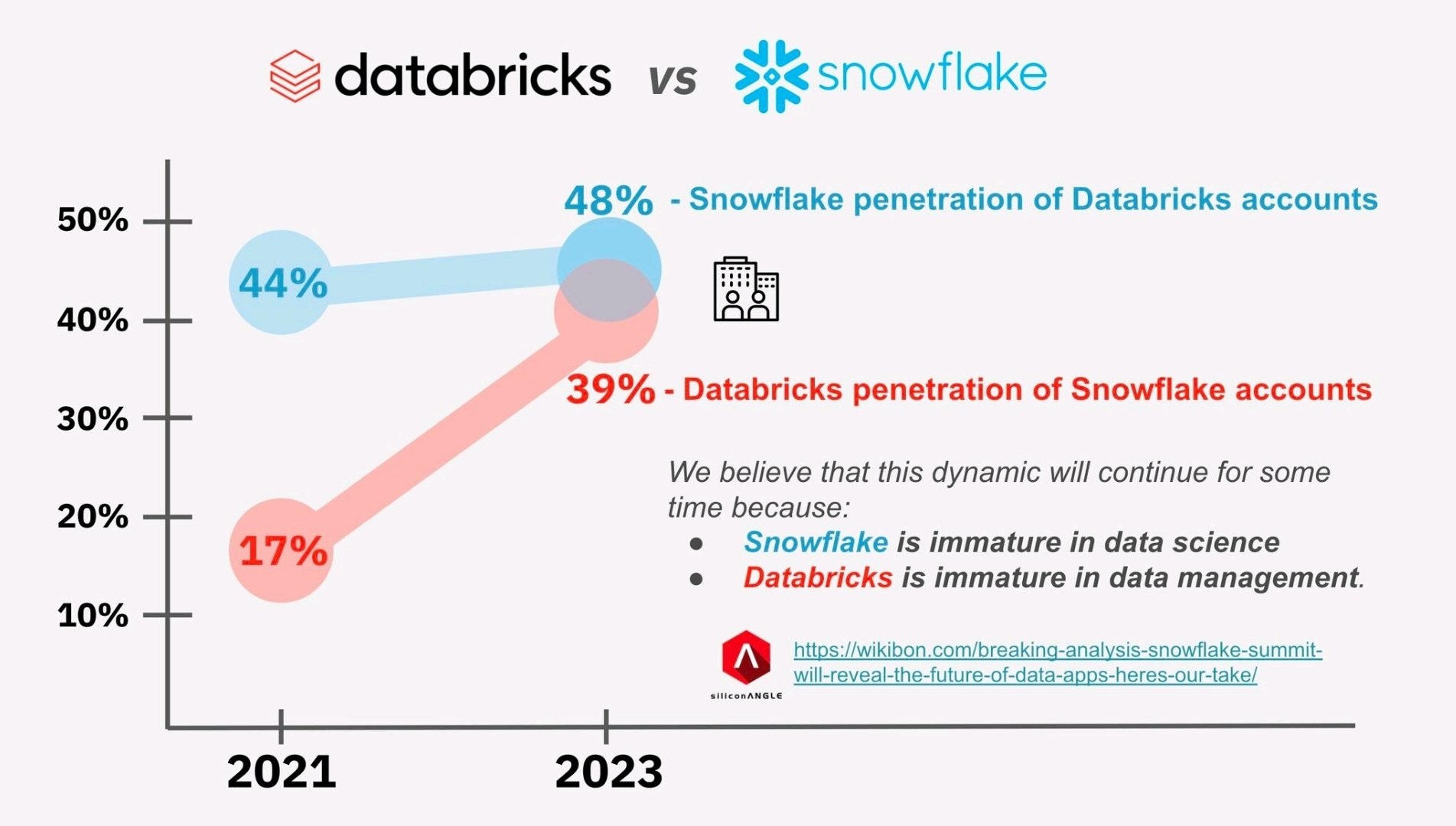

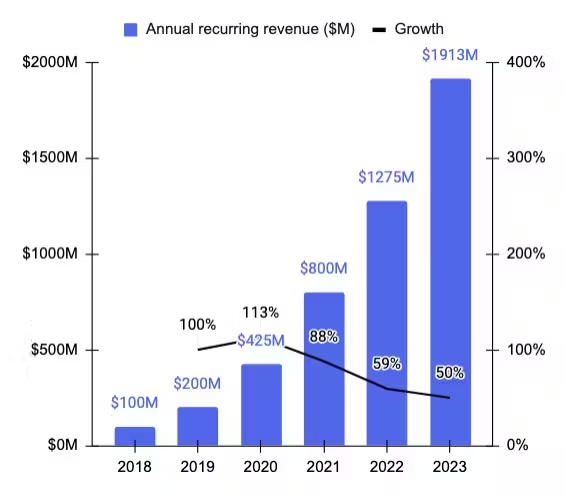

One possibility is that Databricks goes public, achieving a market valuation of $100 billion within the first week of its IPO. This phenomenon would then attract global market attention, and it might ultimately be attributed to the company's "open-source" nature. Given the significant difference where Snowflake's growth rate had already dropped below 30% when it reached $3 billion in revenue, but Databricks, with $2 billion in revenue, still maintains a growth rate of around 70%, people would be unsure about the specific reasons. As the market speculates on what distinct practices set Databricks apart from Snowflake, the conclusion might be drawn that the reason lies in "open source".

Another possibility, based on my observations, is that many enterprise software companies—especially those that have achieved strong commercialization in North America—will realize that open source is indeed a critical factor in their commercialization process. Open source is not devoid of commercial value. While simply hyping up the number of stars on a repository has little correlation with commercial value, the impact of open source on improving the efficiency of software commercialization is evident. Open source acts more like an amplifier for a product’s commercialization capability. If a product inherently meets demand and fits within budgets, open source will amplify that value. However, if a product lacks a budget or fails to meet enterprise needs, then even with open source, it may receive widespread attention but fail to generate revenue—many people might use it, but few enterprises would be willing to pay for it.

3.2 During downturns, should companies still leverage open source for growth? (How to build confidence in open source and maintain continuous investment)

Here is a positive example of benefiting from open source: During the past year or so of the AI FOMO period, an analytical database startup in the open-source infrastructure field in the United States achieved revenue growth far surpassing most AI startups in China and even many in the U.S. The company generated considerable revenue with very minimal sales efforts and also gained dozens of well-known top-tier companies in North America as open-source users, most of whom have already become paying customers. If the company had been using closed-source software, it might have had to follow a "rural encircles urban" strategy, starting with small and medium-sized customers. However, because of open source, it was able to secure the world's leading enterprises as its software users from day one.

In the past, Chinese open-source software companies were rarely perceived as achieving large-scale commercialization. This was mainly due to unclear product positioning and the insufficient organizational capabilities of their teams, not because of any fault with open source itself. If you give the "open source" tool or weapon to a strong founding team, once they break through the early commercialization threshold, they can then enjoy the dividends brought by open source. However, most founding teams in the past were unable to cross that commercialization threshold and got stuck before reaching it. As a result, most companies failed at the very first step. Over the past few years, we’ve seen many teams hyping the "open source" concept, but their real intent was just to secure funding, without genuinely understanding how to leverage open source to accelerate commercialization.

Therefore, China does not lack application scenarios or technical capabilities; what we lack is a favorable business environment and a proper understanding of open source. Thus, while it is meaningful to discuss China's open-source technology, when it comes to discussing the commercialization of open source in China, the reality is that in the Chinese market, open source is only related to refining and iterating products, and has little to do with commercialization. When open source and commercialization are discussed together, it is essentially about the software markets in developed countries with high per capita GDP.

3.3 How should companies balance their resource investment in open source at different stages?

To summarize in one sentence: Open source is merely a lever—first figure out how to commercialize without the lever, then use open source as the lever to amplify it.

However, most open-source software companies in China have already deviated from the correct growth path. Many companies believe that as long as they make their open-source community active, increase the number of users, attract more developers, and accumulate more stars, customers will naturally come to them. The reality, however, is that even if the number of users is very high, whether those users will pay remains a question. For the few paying customers, the size of their contract value is another question. Whether those customers will continue paying in the long term is yet another question. And all of these issues are actually unrelated to open source itself.

They have overlooked the critical questions: Why would customers purchase their product? How much budget have customers allocated for them?

Without a clear budget and purpose, even if a project garners a million stars, it will be of no use. I believe the core premise for a company making an open-source decision is this: Even if I open source the code, I can still sign million-dollar subscription contracts with individual customers in the early stages of the company.

3.4 Some projects secure ample funding during periods of high capital interest but still struggle with stagnant growth. How can they break out of this predicament?

As long as the team has organizational capability, transformation is always possible. The only issue is whether the best and most comfortable timing has been missed. After that, it becomes a hard mode. Once similar products have already risen, the initial cost of breaking into the U.S. market becomes much higher under such circumstances. In other parts of the world, as long as it’s not the U.S., business can only rely on commercial relationships to develop. Only the U.S. market allows a small company to rely on its product to speak for itself.

3.5 How can an infrastructure software company determine whether its technology has the potential to continue evolving in its respective field?

First, if a product or technology can achieve sales without relying on open source and has the potential to secure a million-dollar subscription customer from the very first deal, then it is worth considering further investment in open source.

I believe a million-dollar subscription per customer is a reasonable evaluation standard because, in the enterprise software industry, this is not considered a significant expense. Currently, leading open-source projects such as PingCap, StarRocks, and EMQ all have multiple overseas customers with annual subscriptions worth millions of dollars.

Just because a project is open source does not mean it requires a longer development cycle or that commercialization should be delayed. It should be treated as a regular enterprise software project. Using open source as an excuse for slow commercialization progress is the biggest misconception.

3.6 What is a reasonable timeframe for an infrastructure software project to achieve commercialization validation?

Chinese teams must have a product capable of beginning large-scale commercialization within at least 2 to 3 years after launch. Furthermore, this product must be able to acquire customers and achieve sales in overseas markets to ensure its competitiveness. Otherwise, they will face intense competition and blockades from American and other global competitors. Chinese companies often encounter discrimination when expanding overseas, so they must rely on greater effort to offset such biases.

For American teams, there may be a time window of about five years. American society is highly inclusive, which is very different from China. In the U.S., the industry allows you to make one or two major mistakes, even some that could be deeply painful, as long as the company learns from them, continues to grow, and demonstrates resilience—this is precisely what the U.S. market values.

For example, for an American company, reaching a score of 60 out of 100 might indicate potential for an IPO in the future. However, for a Chinese team, even if you achieve a score of 80, you might still not meet the U.S. listing standards. This is because, during the growth process, Chinese companies face various challenges and discrimination. Since the best markets are not in China, going overseas inevitably involves facing discrimination. For Chinese founders, the requirements to IPO in the U.S. are much higher—if 60 is enough for Americans, then Chinese teams might need to score 90.

4. Through market cycles, infrastructure software remains the best investment target

Guest Speaker: Liu Chao (Atypical Ventures)

This interview with Liu Chao delved into various topics, including software development, startup growth, open-source technology strategies, and innovation in the AI field. The discussion focused on the critical role of technological leadership for startups while highlighting the challenges of transforming technological innovation into commercial value. The conversation also covered the application of new AI technologies, such as vector databases and large models, and their impact on the open-source community and commercial software.

In addition, the discussion explored strategies for entrepreneurs navigating rapidly changing technological environments and how to balance the relationship between open source and business. It showcased the depth and breadth of decisions and strategic choices that technology entrepreneurs must face in complex market environments.

4.1 2024 is yet another challenging year for open-source technology and infrastructure software. What difficulties will it face this year?

My first point is that, as cloud technology has developed for more than a decade, the fundamental concepts and components of infrastructure are now gradually becoming part of history. As a result, the challenges faced by startups have also become more mature and fixed. Those who aim to tackle these challenges must approach them with a relatively sharp entry point, rather than merely offering raw infrastructure. For instance, in the AP space, companies attempting to build data warehouses or comprehensive big data software are now stuck in a quagmire.

This quagmire has two aspects. First, continuous R&D investment is required. Customers are usually unwilling to take on risks without visible results, which demands long-term investment. Second, in terms of commercialization, customers often lack trust in large and heavyweight software developed by small companies. This distrust is justified, as customers not only need the core software but also a mature ecosystem of peripheral products. Developing these peripheral products is more complex than the core software itself and requires extended development cycles, leading customers to perceive the product as immature.

Secondly, in terms of cost and compliance requirements, small companies find it difficult to compete with large enterprises. Regarding cost reduction and efficiency improvement, I believe this is indeed a viable entry point, especially in the current economic environment. However, cost savings alone are not enough—speed and compliance at the product level are also necessary.

For mid-sized companies, I think they can actually leverage globalization to achieve many goals. First, the product must be excellent enough to make mainstream U.S. users choose it over domestic alternatives. This not only tests the strength of the product itself but also places high demands on overall business execution capabilities. Second, it is essential to explore markets that European and American companies are reluctant to touch or tend to overlook, such as Japan, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia. Actively expanding into these markets makes a lot of sense.

Cost reduction must be achieved through technology rather than relying solely on pricing strategies. If you simply lower prices, buyers will not choose you; instead, they may perceive you as lacking confidence or expect you to further reduce prices, making them even more hesitant. To reach the level where this approach works, it undoubtedly requires an outstanding product.

4.2 Has the capital market adjusted its expectations for infrastructure software?

I never have high expectations for the speed of technological software development, even at different stages of development. First, product research and development itself takes time. Second, the process of user trials, interactions, and decision-making also requires time. From what I’ve observed, the fastest development cycle is no less than nine months, and in most cases, it exceeds 12 months. Therefore, software development is not particularly fast.

Once data and voice technologies reach maturity, innovation in the AI field becomes the true driving force. Every month, we hear customers mentioning various new things, which indicates that they are trying out different products. I believe that open source in the AI field is very similar to the open source movement in big data a decade ago. Open source can greatly accelerate the rapid innovation of new technologies and facilitate widespread adoption by users.

4.3 How should infrastructure software companies decide whether to open source?

I believe there is more than one path up the mountain. This includes decisions such as which protocol to use for open source or at what stage to choose open source. We often see many code forks and changes in protocols, and these changes actually reflect the commercial needs of companies. When making decisions, business demands are always the primary consideration.

In this process, the purpose of open source is multifaceted: first, to acquire users; second, to refine the product; and finally, possibly to seek support from external development teams. These three aspects are usually prioritized in the minds of founders. Therefore, whether to open source early, in the middle stages, or to start closed source and then open source, there isn’t a fixed requirement. However, I believe there are a few common understandings that are necessary. First, we should categorize software globally into AI, non-AI, and software at the forefront of AI. In reality, pre-AI software exists in a very mature world—it is already highly developed. Users also have a rational attitude towards open source; they seek the best product, regardless of whether it is open source or not. At the same time, their expectations for the best product are very high, which leads to delays in early-stage investments.

Regarding the various aspects we’ve discussed in the big data field, I think the current market has extremely high demands for stability. Compared to ten years ago, when people were less concerned about software stability and could accept manual intervention in operations or rely on patching to keep systems running, the situation has changed. If absolute stability cannot be guaranteed, it might be an issue with the internal engineers on the client side when it comes to decision-making or execution. As a result, their requirements for the stability of open-source software have risen to this level.

The second key factor is emphasizing ease of use, cost savings, and what is known as cloud neutrality, which has become the baseline. However, the highest demands are for stability and compliance. In this context, as users raise their expectations for stability and compliance, they are also gradually becoming accustomed to paying for software, which brings us to the current state.

To summarize, for infrastructure products, large, mature, and historically needed products are more likely to be adopted. The second category includes products with high requirements for maturity, stability, and compliance, where users are willing to pay. The third category involves products that are cloud-native, low-cost, and easy to use. However, in the emerging AI field, the market has the highest demand for rapid product iteration. Users are eager to use cutting-edge technology and may temporarily set aside requirements for stability and compliance. We have already seen many examples of this.

4.4 How should companies determine which parts to open source, as well as the extent and method of open-sourcing?

I firmly believe that core technologies should be open source, while products should remain closed source. The primary value of a product lies in the accumulation of man-hours, whereas the greatest value of core technology is in its design and know-how—knowledge and cognition—which, in the internet age, are essentially free because they spread very quickly. If a certain cognition or method is not widely recognized, it cannot form a barrier or advantage. Therefore, I believe that if the essence of something lies in cognition, know-how, design, or frameworks, it is fundamentally akin to books, which will likely all be freely available in the future.

The concept of "copyleft" exists because of "copyright." As I mentioned earlier, if a product requires many outstanding engineers to spend months or even years accumulating effort—similar to building a house—you cannot give the house away for free, but you can provide the design blueprints for free. This type of software, due to the man-hours behind it, should be treated as such. Furthermore, it may also meet some of the paid needs of commercial users, so charging for it is reasonable. If we are to discuss the open-source decisions of commercial companies, Databricks is undoubtedly the best example.

When a company needs something to build consensus or meet the needs of enterprise clients, it inevitably operates within different product matrices across multiple dimensions. As a home-run player in the big data field, it has both open-source and closed-source components at different levels, and it has also undergone changes in licensing. Therefore, studying it as a case in depth can help us understand these related changes. Specifically, when we collaborate with venture studios to make decisions, we are always very cautious. Every role involved will engage in extensive discussions, and modifications will be made after these discussions. We dive deep into the matter and then step back to reassess.

Moreover, companies also reflect certain individuality and individualism internally. In reality, the concept of "person" is not merely a pure triangle; the value orientation of the founder also influences the company’s direction.

4.5 How can companies validate the impact of open-sourcing and make necessary adjustments?

For commercial companies, from the perspective of capital, the essence is ultimately about returns. If it involves computational software or open-source software, I would set expectations based on the scale of the project: at least five years to see initial results, seven years to witness significant progress, and within ten years to achieve tangible returns. Regardless of whether it’s developing software or starting a business, it is never an easy endeavor.

One of the appealing aspects of infrastructure-focused startups is that they are built on challenging technologies. Although they take longer to develop, the results are often highly impactful. If you already have deep experience in cloud and data, it naturally becomes an excellent field to pursue. Additionally, nearly every company is contemplating how to integrate their business with AI.

The type of technical and operational talent I greatly admire are those who, due to their broad and deep understanding of technology, are able to propose new technical directions, or those who possess strong research acumen and taste, allowing them to identify promising development paths. However, this combination of solid foundational knowledge and visionary technical insight is extremely rare in the market. It is highly sought after and admired by everyone within the industry.

4.6 In the current macro environment, what promising aspects of infrastructure software are still worth investing in?

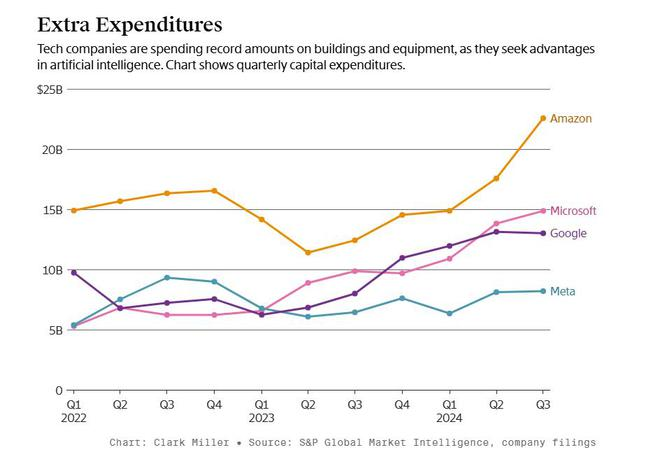

Investors primarily focus on commercial value. They have recognized the value of infrastructure, having previously invested in data infrastructure and cloud infrastructure. I believe AI infrastructure will also be very successful. First, I hold a positive view of AI and believe that current large models have already demonstrated powerful capabilities and usefulness—the foundation is already very practical. Now, people need to realize that it is still accelerating in growth and consider whether it can become even more powerful. Therefore, I have a positive attitude toward infrastructure. From the perspectives of economic value, social impact, and technological advancement, I think it is very promising.

I believe no startup can last forever, because entrepreneurship itself is extremely difficult and filled with anxiety. Very few people can endure it like running a marathon, so they need to achieve phased results. However, regarding the second and third points, I think people have indeed learned a lesson: in the AI field, technological leadership does not directly equate to company value. In the more mature data and cloud computing markets, technological leadership must be translated into the aspects we previously discussed.